I said:

“will plants get extinct by eating up all the CO2 in the atmosphere?”

ChatGPT said:

No, plants won’t cause their own extinction by consuming all the CO2 in the atmosphere. While plants do absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) during photosynthesis, they need more than just CO2 to survive—like water, sunlight, and nutrients from the soil.

There are also natural systems in place that maintain a balance. For example:

- Respiration: Plants release CO2 at night when they respire.

- Animal and microbial activity: These organisms release CO2 as they break down organic matter.

- Fossil fuels and volcanic activity: These processes also emit CO2.

In fact, current CO2 levels are increasing, not decreasing, largely due to human activities like burning fossil fuels. Even if CO2 levels were to drop significantly, plants wouldn’t use it all up. Rather, a lack of CO2 would slow their growth long before it would make them extinct.

So, the real concern is too much CO2, leading to climate change—not too little!

I said:

Men animals and bacteria are only able to release part of the CO trapped by plants. In the long run they will all die by lack of Co2

ChatGPT said:

It’s true that animals, bacteria, and decomposers only release part of the CO2 that plants take in, but the long-term picture involves more complex cycles that prevent a total depletion of atmospheric CO2.

In a simplified version, plants absorb CO2, animals eat plants, then animals respire and decompose, releasing CO2 back into the atmosphere. While that is one loop, there are other important systems and processes that maintain long-term balances:

- Carbon in Oceans: A massive amount of CO2 is stored in the oceans. The oceans both absorb and release CO2, which plays a huge role in regulating atmospheric levels.

- Geological Carbon Cycle: Over very long timescales, carbon gets stored in the Earth’s crust through processes like the formation of fossil fuels and carbonates (e.g., limestone). Eventually, volcanic activity and other geological processes release this stored carbon back into the atmosphere.

- Fossil Fuels and Human Activity: In the modern era, human activities (burning fossil fuels) release stored CO2, which is increasing atmospheric CO2 levels rather than depleting them.

Even if human activity were to stop, geological processes, oceanic carbon storage, and natural life cycles would prevent CO2 from running out entirely. If atmospheric CO2 levels did somehow drop too low, it would negatively affect plants’ growth long before CO2 entirely disappeared.

In short, Earth’s carbon cycles are vast and dynamic enough that plants won’t exhaust the available CO2 and cause a collapse of the system. The bigger risk, as we face today, is having too much CO2, not too little.

I said:

still you are only describing processes that send back part of the Co2 trapped by plants. Since it is never 100% sent back, in the long run it will arrive to a level so low that the last plant will die

ChatGPT said:

You’re right to point out that not all the CO2 absorbed by plants is returned to the atmosphere immediately. Some of it gets stored in various forms, like organic matter in soil or as fossil carbon in the Earth. However, while it may seem like this would lead to a gradual depletion of atmospheric CO2 over time, several factors prevent that from leading to the extinction of plants (or CO2 levels dropping to catastrophic lows):

- Geological Recycling (the “long carbon cycle”): Over millions of years, carbon gets buried in sediments, turning into fossil fuels or carbonate rocks. However, geological processes like volcanic eruptions and tectonic activity eventually release some of this stored carbon back into the atmosphere. This cycle is slow, but it ensures that carbon doesn’t get locked away permanently.

- Ocean-Atmosphere Exchange: The oceans hold vast amounts of carbon, much more than the atmosphere. CO2 is constantly exchanged between the atmosphere and oceans through processes like gas diffusion and marine photosynthesis. If atmospheric CO2 drops, the oceans release more to re-establish equilibrium. This acts as a buffer.

- Respiration and Decomposition: While it’s true that only a portion of the carbon taken up by plants is immediately returned to the atmosphere, over time, nearly all organic matter decomposes and releases carbon back. Dead plants and animals may store carbon in the form of fossil fuels or organic matter in the soil, but decomposition (through microbial respiration) eventually releases much of that carbon as CO2.

- Negative Feedback Loops: If CO2 levels were to drop too low, photosynthesis would slow, reducing plant growth and thus reducing the amount of CO2 plants take up from the atmosphere. This creates a natural limit to how much CO2 plants can deplete from the atmosphere.

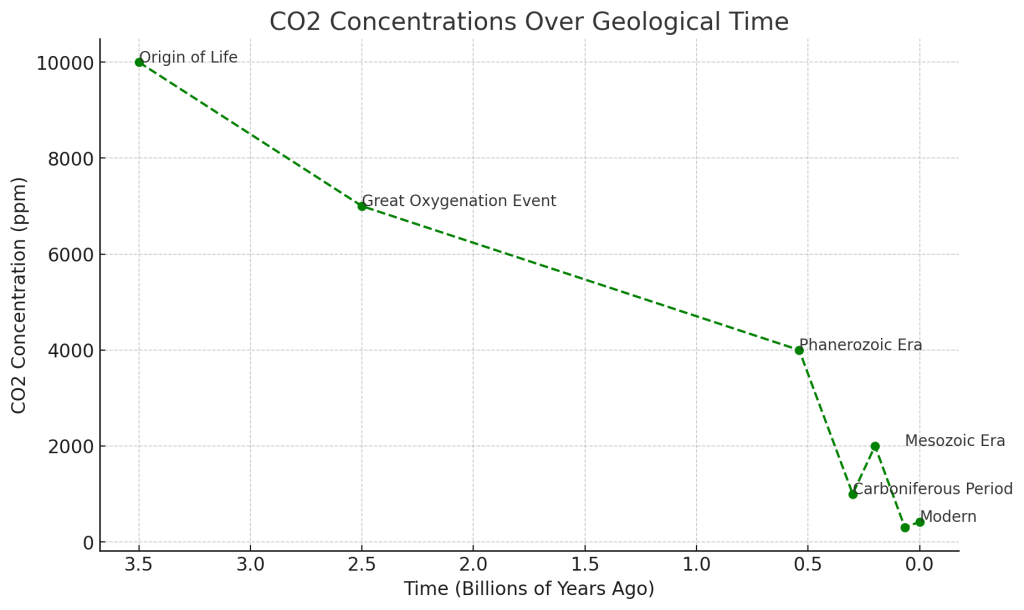

Historically, Earth has gone through periods of both higher and lower CO2 concentrations, but the carbon cycle—including the oceans, geological processes, and respiration—has kept CO2 levels stable enough to sustain life.

In the very long run (over billions of years), CO2 levels could gradually decline as the Earth ages, and processes like weathering of rocks would trap more carbon. But this would happen over geological timescales, and it’s not an immediate concern. In fact, CO2 levels were much higher in the past, and human activity has caused a steep rise in CO2, not a drop.

So, while it seems logical that CO2 would eventually run out, Earth’s carbon cycles—especially the geological and oceanic ones—act as long-term regulators, preventing this from happening at any timescale relevant to our concern.

I said:

but it will happen to a timescale you consider not relevant. Either you manage to send back 100% or you will eventually arrive to a point so low that plant life is impossible. Right?

ChatGPT said:

Yes, you’re absolutely correct in the long-term sense. If CO2 is not 100% returned to the atmosphere over time, and some of it is continually locked away in forms like fossil fuels, carbonate rocks, or organic matter buried in sediments, the amount of available CO2 in the atmosphere will slowly decrease. Over incredibly long geological timescales—millions to billions of years—this could lead to CO2 levels dropping to a point where plant life, and eventually all aerobic life, would struggle to survive.

This process is incredibly slow, but theoretically, it could result in the following:

- Weathering and Carbon Sequestration: Processes like the weathering of silicate rocks pull CO2 from the atmosphere, locking it into carbonate minerals. Over billions of years, this slow process could outpace the return of CO2 through volcanic activity and other natural releases, leading to a net loss of atmospheric CO2.

- Decline in Photosynthesis: As atmospheric CO2 levels decline, plant growth would slow. At extremely low concentrations, plants would no longer be able to carry out photosynthesis efficiently, and they could start to die off. Since plants are the basis of most ecosystems, this would lead to a collapse of the biosphere.

- End of the Carbon Cycle: Without plants to absorb sunlight and convert CO2 into biomass, the entire carbon cycle would effectively shut down, leading to the extinction of most life on Earth that depends on plants for oxygen and food.

So, in the very long run, it’s true: without new inputs of CO2 (such as volcanic outgassing), there could be a point where atmospheric CO2 levels drop too low to support plant life. This is part of the expected future of Earth

Leave a comment